BY TOM NELSON

On June 15, 1920—in less than a day’s time—three young Black men (Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie) were wrongly arrested; ripped out of their jail cell by a vicious mob; taunted, tortured and dragged to a lamppost; and mercilessly murdered. Lynched. It didn’t happen “Down South;” it happened here, in Duluth. Thousands of White Minnesotans were involved. This coming June 15—100 years later to the day—in a deliberate act of remembrance and with a community-wide commitment to learning and hope, we will gather in Duluth to mark those murders and to move forward together. We will do so again the next day in Minneapolis. Please join us. Here is some background.

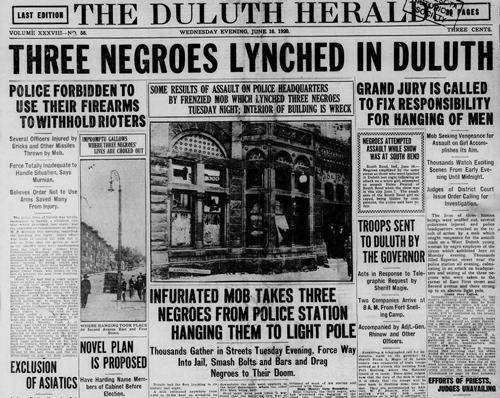

The basic facts are lawless and brutal. For some unknown reason, Irene Tusken claimed that six young Black circus workers raped her on June 14. Her doctor examined her, and later testified that she had not been raped or otherwise assaulted. The next morning, June 15, thirteen Black men were apprehended by the police as the circus was leaving town; seven were released; six were jailed. That evening, the Duluth Herald headline read: “West Duluth Girl Victim of Six Negroes.” A mob of thousands gathered outside the jail (having been urged to “join the necktie party”); overcame the police; broke into the jail; conducted a “trial” on the spot; dragged three of them up the street to their ghastly deaths; posed for souvenir photographs; and left their victims dead at the lamppost. “Strange fruit,” as Billie Holiday would later sing. Judges Cant and Fesler tried to stop the slaughter; as did Attorneys McClearn and McDevitt, and Fathers Powers and Maloney—only to be told: “To hell with the law!” and “We don’t care if they are innocent or not.” The bodies were removed the next day, and taken to Crawford Mortuary (after another mortuary declined to help). They were buried in unmarked graves—a wrong only recently righted.

Three men were convicted of “rioting,” but served light sentences. No murderers were ever convicted of the murders, despite thousands of eye witnesses. Some members of the media were outraged; others excused, justified, or even tried to explain the “benefits” of the lynchings.

There was and is no excuse, of course. The throng of Minnesotans that night in Duluth did not lose their minds or misplace their consciences. They knew what they were doing and they intended to do it. The pictures show their individual faces—some somber and others smiling, seemingly proud of what they had done. Individuals don’t get to blame, or hide in, some sort of “mob mentality.” We lawyers know that. Mob Rule is, after all, the exact opposite of the Rule of Law.

Between the 1870’s and 1950’s, there were more than 4,500 terror lynchings in America. Those lynchings were intended to create fear. They were spectacles meant to be seen and to convey a message—with children on parents’ shoulders for a better view; sometimes with the local Black population forced to watch. They were performed in the presence of the purported Rule of Law, and sometimes with its permission—often in the public square; sometimes on a courthouse lawn. The killings took place while statues were being built (purportedly to honor those who fought for “the lost cause,” largely during the 1890’s to the 1920’s, and notably again during the Civil Rights Era of the 50’s and 60’s), and while federal anti-lynching statutes were being resisted (filibustered in the U.S. Senate, citing the canard of “racial favoritism” or promising enforcement under states’ rights). The lynchings could only have happened by viewing people of color as some sort of unworthy “Other,” not as fellow human beings. A reminder of the need for vigilance, even today, when incidents and policies seem afoot to “otherize” still others.

As the Duluth killers proudly sought a photographic trophy of their treachery (suitable for postcards, which promptly flew off the shelves of Duluth merchants at 50 cents each), one of the lynchers yelled out, ironically and aptly: “Throw a little light on the subject!” Headlights illuminated the scene for those preening to be seen. That photograph cannot be un-seen; nor should it be. As Ida B. Wells said so well: “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” History can be a light in its own right, helping us face forward into our future together. That’s what the coming months hold: not just noting history, but making history.

This is all such a sobering part of our history; sickening, really; but also strengthening—if we learn from it. As it turns out, Duluth was the very first community in our nation to build a monument to honor its lynching victims. The Clayton-Jackson-McGhie Memorial is a dignified and moving plaza—taking back the corner of First Street and Second Avenue South (one block up from Superior Street), across the street from the site of the 1920 murders. Engraved into the walls, in bold letters, it says: “An Event Happened Here Upon Which It Is Difficult To Speak And Impossible To Remain Silent.” Sculpted into the walls are images of Mr. Clayton, Mr. Jackson, and Mr. McGhie—not as they were in that photograph, but instead standing tall and strong. That memorial calls for you to visit. www.claytonjacksonmcghie.org

These coming months (and June 15 and 16, in particular) will include unique, important, moving, and motivating moments.

- On June 15 in Duluth, Bryan Stevenson will speak at the site of the lynchings. He is the author of “Just Mercy” and the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama—site of the national lynching memorial. A sacred place. www.eji.org

- Earlier that Monday, there will be an extended public program at Duluth’s courthouse plaza. Minnesota federal courts will be closed that day, in honor of the commemoration proceedings. Judge Richard Gergel, author of “Unexampled Courage,” will join us.

- On Tuesday, June 16, at the Minneapolis Hilton, Bryan Stevenson and Judge Gergel will speak to us again.

Please mark your calendars to join us as we mark these moments—and as we move forward together.

TOM NELSON is a partner at Stinson LLP (formerly Leonard, Street and Deinard). He is a past president of the Hennepin County Bar Association.